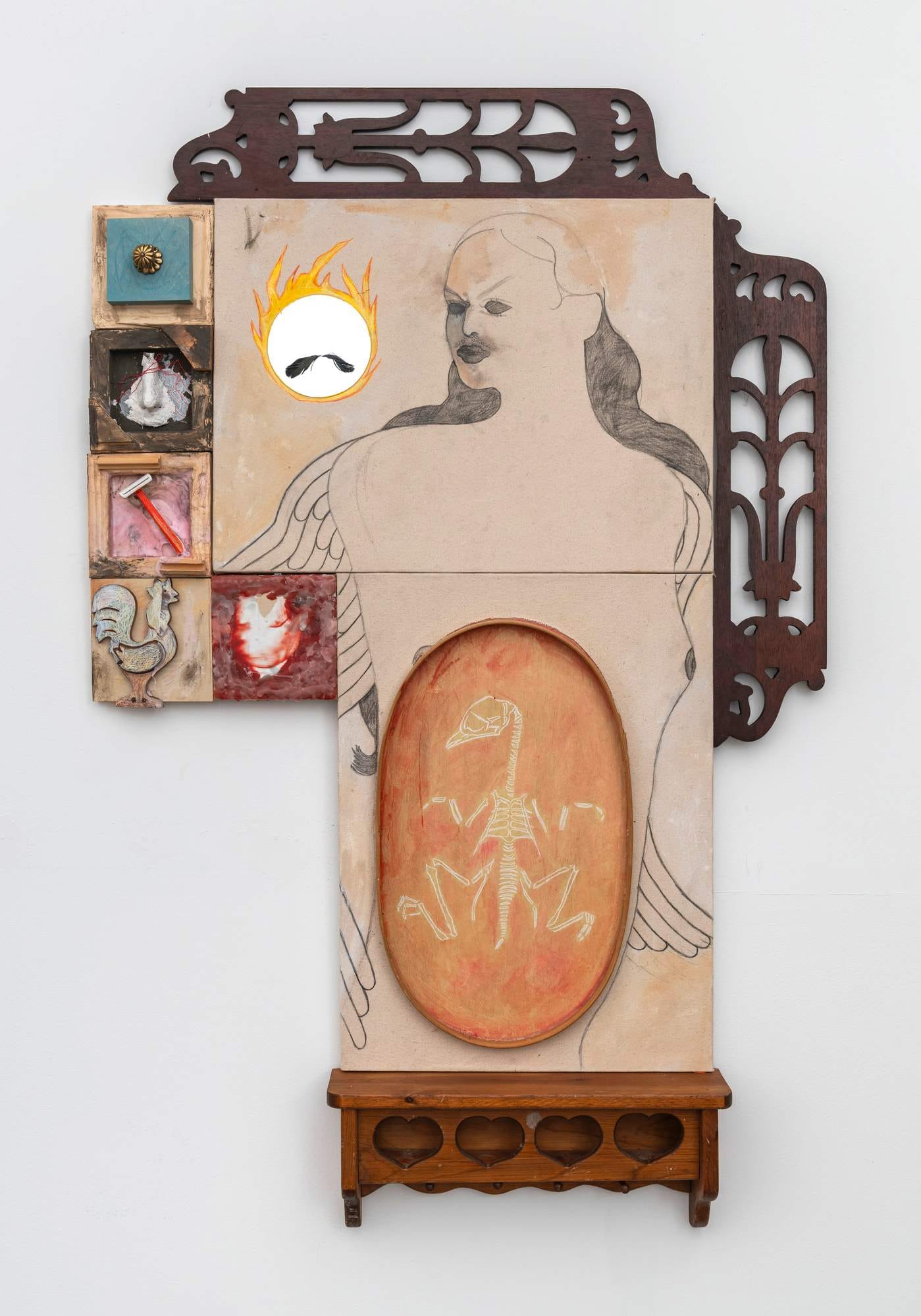

New York-based painter and sculptor Amy Bravo doesn’t want to be subtle. Through her multimedia work, she toes the line between the absurd and the grotesque, oscillating “between kitsch, a Dada-esque sense of humor, the readymade, and a queer kind of campiness.” The result is a distinctly Bravo universe—populated by mythical creatures, archetypal symbols, and an army of giant, machismo-fighting women.

In our conversation, we explore queerness as revolution, the evolution of the modern fable, and the question Bravo has been reckoning with for years—and might finally have an answer to: Would my ancestors like me?

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

ISABELLA FOX ARIAS: Looking at your recent pieces, I see them populated with archetypal animals—the bull, the rooster, the spider, the horse—figures that echo across fables from many cultures. What draws you back to these creatures? What do they represent to you?

AMY BRAVO: It's funny that you say fables, because that is one of the reasons why I’m interested in them. Usually, these stories come from my family. My family has a farming background in Cuba. My grandparents used to live in a hut and slept on the floor, and they ranched cattle and chickens. The myology of the farm is really interesting to me—the magical realism that exists with it all. I grew up in New Jersey, so it’s not really part of my vernacular. What started me using these motifs was the family connection, but I was also drawn back to them because they are creatures from a fable. They are used for the most remarkable stories of all time.

Along with your animals, your figures feel quite archetypal as well. They often share the same expressions. They have these dark, menacing eyes, and then equally dark little nipples. By returning to the archetypal, you seem to be removing identity. Who are these figures? Are they reflections of yourself? Women in your family? Why did you choose to remove specific identifying features?

I think when I first started making my figures, I thought about how I and know a lot of my extended family on the Cuban side. There was this sense of loss, of not having that community. So I was trying to create people who felt familiar—people I knew I’d get along with. But in doing that, they started to look more and more like me. Because really, you mostly get along with yourself—and even then, not always.

So they became these clones of each other. And when I realized that, I thought, this is ridiculous. I had dehumanized them to the point where they weren’t even people anymore. That’s when they started to feel like a secret society—like an army. It was like playing a video game where you make the character stronger and cooler than you. They became the people I would send out into the world of my work to cause trouble on my behalf.

At some point, I started blacking out their eyes. There was too much actual life in the eyes, and it became clear to me that these people had never been alive. They needed this blank, rinsing gaze.

I also look a lot at 1930s strongmen and wrestlers for physical reference. I think that’s because I’m short and feminine, and I’ve always wanted to move through the world like a giant woman with huge muscles—someone who could crush someone with her fingers but also has long, flowing hair. These figures let me embody that.

As you're speaking, it seems like narrative really thrives throughout all of your pieces. Can you tell me more about your storytelling process?

My worldbuilding process happens intuitively, alongside research I was doing into my ancestry, mythology, and all of the elements you see in my current work. I don’t know what the painting is going to say, but I’m going to work with my existing tools that I know have all these signifiers attached to them to create a painting. The paintings are similar to my sculptures in that everything in front of me gets cobbled together. I can then step back and see something that I wasn't necessarily prepared for, but something I’m excited about.

Your pieces feel incredibly cohesive despite the range of media you use—sculpture, textiles, painting, and you'refound objects. How do you build a piece from the ground up? Where do you source your materials?

The first time I ever did a big project, I was making a painting and sculpture simultaneously. It was in undergrad and I was allowed to have a full room to create an installation. I thought, ‘I’m just going to get a bunch of stuff and put it all together. I’m going to paint the walls, paint the floor, and make the sculptures come out of the wall. I was very interested in the idea that they would be frankensteined into each other. I was also looking at a lot of home altars that people create in their houses and how mundane objects were used to make something that feels, I don’t think spiritual is the word, but I think it's like you're exalting the mundane object to something that's almost ridiculous.

When I make my sculptures, I source materials from all over. Initially, I took stuff from my parents' house, like their old furniture and trinkets. When I exhausted that source, I had to branch out, but everything I use feels like it could have been in their house. It's like a shared language.

As a queer viewer, I see queerness threaded throughout your figures—not through binary gender signifiers, but through traits that feel animalistic or symbolic: the cock, the bull, the spider. How does queerness shape your worldbuilding? Do you see your characters as queer in themselves?

I think queerness has affected my work because it’s affected my relationship to my family. A lot of the time, I’m asking: would my ancestors like me? It’s always a kind of reckoning with that. It’s either—they would love me, or they would hate me. And I have to be okay with both outcomes. Because the figure in the work is sometimes really loving these other family members, and sometimes she’s like—‘fuck you guys, you don’t like me? Whatever.’

The figures—like the rooster and the bull—are stand-ins for these macho archetypes I come from. Sometimes I turn into them, sometimes I attack them, and sometimes I hate myself because I’m turning into them. And I think that’s a very queer thing to do.

Also, the nature of how I make work—it always feels super cobbled together from everything. I think that’s a really queer existence: we create ourselves out of what’s around us. We’re not just accepting what we’ve been handed—we’re trying to pull from everything and build something new.

Your recent show, Transmogrification NOW, at Swivel Gallery, twists the typical fable of the Ugly Duckling into something far stranger by focusing on transmogrification rather than transformation. How do you distinguish between the two? What does transmogrification mean to you?

I was looking at the definitions of metamorphosis and transformation, and I realized—everyone uses those words. How do I describe something that feels a little different? That’s when I found transmogrification. The definition described it as a ridiculous, sudden transformation, and I loved that.

It’s like you just wake up one day and you’re… this new thing. That felt really honest to me, especially in the context of family. Like when you suddenly catch a trait in yourself and you're like, Oh my god, I’m my dad today. It feels like it came out of nowhere. But if you look closer, it didn’t—it was always there. Still, the suddenness of it is what resonates. Like today, I woke up and I was the rooster. And maybe tomorrow I won’t be.

The suddenness of it also played into how the work was made. Everything came together really quickly. I talked about this before—I would just look and know that these things had to come together, and by all means necessary, I would figure out how to make that happen.

Your work combines humor with the grotesque. Humor often gets dismissed in the art world, overshadowed by themes like pain, suffering, and trauma. What role does humor play in your work? How do you walk that fine line between humor and the grotesque, without tipping into parody or punchline?

I think the objects have their own sense of humor, and sometimes the way they're combined is just funny—or so ridiculous you have to laugh. I was thinking about a sculpture of a bull, and I was sitting in my apartment and saw this candlestick, and I thought, oh my God, that's a butthole. I had to get up and grab it.

It’s this idea of walking the line between kitsch, a Dada-esque sense of humor, the readymade, and a queer kind of campiness. A lot of the time, I’ll make these cowboys who are completely decked out in rhinestones. The last one I made for that show had a swinging machete between his legs. It’s all pushed to a certain level of ridiculousness. I don’t want to be subtle.

In past interviews, you’ve mentioned Cuban artist Belkis Ayón as a major influence. A year before she died, she said: “These are the things I have inside that I toss out because there are burdens with which you cannot live or drag along. Perhaps that is what my work is about — that after so many years, I realize the disquiet.” Does that idea —of tossing out what burdens you — resonate with your own process? What kinds of disquiet are you working through in your practice?

I've been calling each piece a vessel—it really does feel like a vessel for a certain feeling I might have toward a person. And that feeling can change on any given day. Sometimes it’s even a feeling I have toward myself.

I really think that the period of time when I’m making the work feels like a period of conflict. And instead of being in conflict with other people or with myself, I’m choosing to be in conflict with a series of objects that are endlessly frustrating me—or with images that are frustrating. The process of bringing them to life and taming them into existence becomes this negotiation. Reaching an agreement. And that’s usually how I feel at the end of a piece. Is it done? That’s not really the point. Have we agreed? Yes. Once that happens, I feel like something lifts. I’m able to do a lot of emotional work through making the work.

At this point, I’ve done so much processing around that feeling of wondering if my ancestors would like me, support me. I’ve unburdened that part of my life. And now what I do comes from that place of having worked through it. That’s why it feels like a new chapter is opening up in the work.

So many artists end up making work about the same wound over and over. There are always moments where it’s reignited—but right now, I feel like the work has done what it needed to do. I’ve made peace with that question. So now I’m pilfering through the other parts of my life that still need to be expunged through the work.

Belkis Ayón’s work has been important to me since undergrad. I had a really great professor who introduced it to me. What first excited me was the way it came out of the wall. There’s this one piece of hers called To Make You Love Me Forever, and the bottom of it almost feels like a skee-ball ramp—it lifts your eye up to the image. That created a totally different relationship for me. It wasn’t a painting, it wasn’t a sculpture—it felt like a page of a book that was unfurling itself onto you.

She had this retrospective that’s been touring, and the way the work was installed was amazing—each piece was double-sided, and you walked through them. The whole room felt like these stage sets, or backdrops for plays. And when you walk between them, you're in it. You’re not just passing by—it’s not a window you’re peering into. You’re actually between these people on the pieces. You have a completely different relationship to the work that way.

She talks so much in her work about being a transgressor in a secret society—being the lone woman in a society of men. And I think it’s funny that she makes you as the viewer do that, too. You’re walking through the secret society of her work, but you’re not really a part of it.

You mentioned secret societies earlier—the secret society of your women. Do you think that maybe part of that comes from thinking about the secret society in Belkis Ayón’s work?

Yeah, I definitely think so. I think she really nurtured that idea—that it could be an army of women. I love the idea that they’re all moving together, like their body movements might be synchronized, or they’re egging each other on to cause trouble. That’s really funny to me.

And it’s also true to my life. An ex once told me that I had structured my whole life around women, and that men were just arbitrary figures in my world. And I was like, yeah... that’s pretty accurate. In the work, that becomes even more extreme. I always joke that I wish I could live in a world—or a bubble—where there were no men. So I created that world in the work.

With everything going on in the US right now—politically, socially—it’s become harder to create. As an artist myself, I’ve felt at a loss with my painting over the past few months. How are you staying grounded through it all? What keeps you motivated to make work?

I’m in a place where I’ve intentionally slowed down. But even before everything got really intense, I had been saying for months that I needed a break. I had just done three solo shows basically on top of each other.

Congratulations! That’s amazing.

Thank you! But I kept telling everyone, “You’re not ready. After this show, I’m taking a huge break.” And then… when the break finally came, it was like—oh. Everything's getting really scary and bad right now.

So it became really hard to actually quiet down. To even be able to do that—to rest—feels like a massive luxury. I feel so much financial pressure. Being an artist in New York is just… intense. There’s pressure to stay here, pressure to keep making, and everything’s more expensive than it’s ever been.

I spend a lot of time reckoning with my fear of the future. And I think that’s probably going to be embedded in the next body of work, because it feels like the next final boss in this video game I’m in.

I try really hard to keep my community of kickass women around and alive—and that’s the only thing that feels nurturing right now. I live in a very Hispanic neighborhood, and it’s scary knowing we’re being targeted. The women who work at my grocery store, the people who walk down the street next to me—I think about them constantly.

But at the same time, this is the first time I’ve ever lived in a place where everybody looks like me. And it’s this strange thing—this joy and this grief happening at the same time. I wish it weren’t happening at a moment when I feel so aligned. Every day is a struggle. There’s no clear answer right now.

But I do think we need to keep our communities strong. We need each other more than ever.