Speaking with Joanne Leonard is nothing short of a complete and absolute pleasure. It’s rare to encounter an artist who is so open and generous with her thoughts – especially after such a long, prolific career. Working since the early 1960s, Joanne has been at the forefront of both the feminist and civil rights movements. These themes run throughout her body of work, particularly in her pioneering “intimate documentary” photographic style and her groundbreaking collage practice.

Like many brilliant female artists, Joanne has only begun receiving widespread critical recognition in the past two decades. Her work is now held in major contemporary art institutions, including MoMA, the Met, and the Whitney. And now, for the first time, her work has crossed the Atlantic: on view from May 30th at HackelBury Fine Art in London. The V&A has also just acquired a collection of her photographs, which represents the first European acquisition of her work.

In our conversation, we explored feminism, photography, the bureaucracy of museum collections, and how to keep making art – even when it feels impossible.

The text has been edited and condensed for clarity.

ISABELLA FOX ARIAS: When did you first start taking photos? What drew you to photography?

Joanne Leonard: When I was about eleven, the “Family of Man” exhibit came out. Do you know about that?

No, I don’t.

It was put together by Edward Steichen and circulated around the country – maybe even internationally. It was a post-war gesture that aimed to show how we’re all one family. The idea was that if we could understand that, it might lay the groundwork for not having more wars. It was a very idealistic idea. There was a giant book that, when I babysat, I’d see on people’s coffee tables. Eventually, it was published as a paperback for a dollar, and I had my own copy.

The exhibit itself was designed so that there were no borders or mats – the photographs were enormous, and you walked through an environment of photographs [at Barnsdall Park, which became LACMA] It made a huge impression on me – the power of the photographs, the mission behind them. It was very flawed – there was no analysis of class or economics or government – but it was powerful for a kid.

I imagine we’d all bristle today if someone called an exhibit about ‘mankind’ The Family of Man. Back then – —in the early 1950s – —‘man’ was meant as shorthand for ‘human beings,’ but I doubt we should even use the term ‘mankind’ today. Later, books were published as sequels – —The Family of Women, The Family of Children – —and I have work in each. Later still, books like Women See Women and Women See Men tried, in their own ways, to reflect on human experience through photography – —and my work appears in those as well.”

Do you think, with your work, you try to create an environment of photography like the one you saw in that exhibit?

Oh, no. I think long ago I bought into the idea of a plain white mat and the more contemplative notion of individual photographs set apart. I wanted photographs to be art. That was part of the gesture.

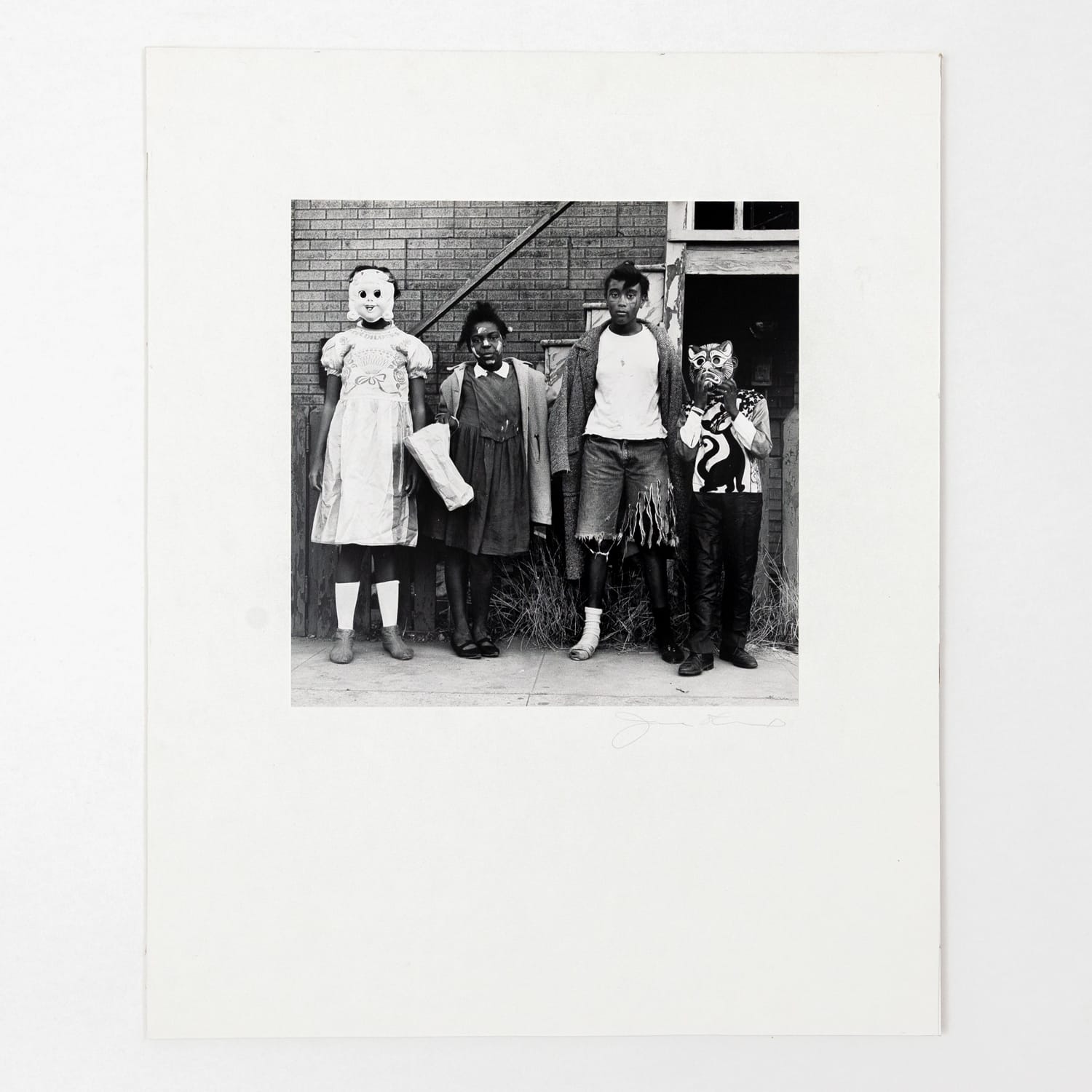

Can you tell me about your early years in West Oakland with your partner? I know your neighbors became some of your first photographic subjects, but I’m interested in how you built those relationships. How were you able to walk into that community and get people to open their lives to you?

Well, we lived there. It was an industrial building that had been a flour mill, then a Boy Scout headquarters. It was abandoned when my husband, a sculptor, bought it. He was part of the DIY culture in California – he restored plumbing, electricity, and finished floors. So we had a very nice living space inside a building that didn’t look like a house. Kids would come by and say, “You live there, lady?” They saw me every day, but it didn’t make sense to them.

In front of us were houses that were not in great condition – very minimal in terms of comfort. During WWII, people had come from the South to Oakland to work for Kaiser Industries. The housing was segregated – they couldn’t live in other parts of the city. It’s not a great history. People often owned their homes but didn’t have the resources to maintain them.

The area had been zoned ‘light industrial.’ In addition to houses, there was a salvage yard and a rag-picker nearby. Zoning made it illegal for homeowners to make substantial repairs – especially anything considered remodeling. The city’s plan was for the area to deteriorate so that houses could be removed and replaced by more light industry. So it wasn’t just that residents couldn’t afford to fix their homes – they weren’t permitted to.

There was no garbage collection because there were no sidewalks, curbs, or gutters. And services weren’t provided unless you lived in the "right" part of the city. So we joined a neighborhood organization to campaign for those things. That’s how we met our neighbors.

How interesting!

The organization was sponsored by the War on Poverty – this was around 1963 or ’64. We didn’t meet our immediate neighbors, but people from farther down – like on 11th Street – had more resources. They became our friends. We all worked together politically to push the city for services. That’s how I met people. Some of my earliest photographs were taken just outside my front door or from my upstairs window.

Eventually, I started photographing graduations and weddings – not really featured in the current exhibit, but still part of my work. The Oakland Museum acquired some of that early work. Theresa Heman was the curator there. She was very interested and acquired the first pieces I ever had in a museum. When she got very ill and passed away, she requested that more of my West Oakland work go to the museum.

I held back a few that were especially personal – weddings, family moments – but the majority went. You can look online and see how much is archived. Unfortunately, the museum hasn’t shown much of it. For years, the same one picture would go up when they did show something. It’s disappointing.

Now, however, Makeda Best – formerly from the Harvard Art Museum – is there. She’s interested in the work and said ten of them are going to be shown in an upcoming exhibit. So maybe things are changing.

It’s hard to believe they’ve held so many of your photos and not shown them.

Yes, it’s frustrating. For a while, my West Oakland photos were what most people wanted to collect. But once they were with the museum, they just sat. Other museums have since shown interest. The work has traveled a bit more now, but those early pieces at the Oakland Museum have still never been fully exhibited.

You’ve described your work as an “intimate documentary” style. Can you tell me more about what that means to you?

I’ve always respected the idea of documentary photography, but calling it “intimate documentary” was my way of acknowledging a contradiction. Documentary is usually impersonal, objective. But my work is mostly of people I know – family, friends. I realized I wasn’t cut out for photographing strangers and didn’t enjoy being intrusive. So I stuck close to the people I cared about.

Calling it “intimate documentary” was a way to elevate or give weight to personal work – recording everyday life but doing it with a sense of care and proximity. It was my way of claiming a space for personal, emotionally engaged documentation.

I love that. And I think your work gives equal weight to the private and the domestic – especially spaces usually coded as feminine, like kitchens or bedrooms.

Yes. That started with a documentary project I was invited to join by Chauncey Hare. He had a very politicized idea of photography and was making work about corporate oppression – he got a grant titled “The Impact of Technology on American Lives.” He asked me to join to offer a woman’s perspective.

At the time, I had a 2-year-old daughter and was teaching. I didn’t have the ability to travel far, so I decided to photograph my own neighborhood – my block, my home. I thought: appliances are technology too. Stoves, refrigerators, toasters. I tried to document domestic labor, the machinery of home life, and how that shapes women's lives. It allowed me to work while parenting, and still produce something meaningful.

That leads into my next question – I often struggle to find time to create while working full-time. Do you have advice for artists like me? How did you do it? I do. I completely understand that feeling. For me, the only times I really made progress were during breaks from teaching – spring or summer terms. When I wasn’t teaching, if I had a clear sense of a project, I could make small steps. That’s the key – define what you’re doing. If I knew I was taking photos of stoves, or windows, or something specific, it became easier to keep going.

The more defined the project, the easier it is to make the next piece. And I’ve always preferred working in series – developing an idea over time – rather than seeking a single, iconic image. That sustained approach helped me stay creative in small pockets of time.

That’s excellent advice. Thank you! Okay – something I’ve been very curious about: with your “intimate documentary” style, especially when photographing other people or personal spaces, how do you draw the line between being a documentarian and being a voyeur?

That’s a great question. When I saw it in your list [of questions], I actually looked up the word “voyeur” again, hoping it might give me a clear way to say, “I’m not that,” but the line is blurry. I think it depends on your relationship with the person or place you’re photographing.

The same photo could be seen as voyeuristic in one context and intimate in another. I’ve wrestled with this especially in photographing my daughter. Am I objectifying her? Am I creating distance by putting a camera between us? Or am I showing love and attention? I think she’s felt both at times.

It’s not just how you look – it’s the whole dynamic. And of course, if you’re thinking, “This would be great in an exhibit,” or “Maybe this will sell,” then all those motivations complicate things even more. I don’t think there’s a clear boundary where one ends and the other begins.”

Yeah, I figured it wouldn’t be black-and-white, but I was so interested in your take. Thank you. I also wanted to ask about your use of journals. It seems like a fundamental concept in several of your works – like Journal of a Miscarriage and Newspaper Diary. I never revisit my own journals – they feel too messy, too private. But you seem to use yours as source material. How does that work?

It’s kind of a cheat, honestly – the way I use the word “journal.” I mean, lots of newspapers call themselves journals too. For me, it just means something ongoing. Journal of a Miscarriage wasn’t strictly daily, but it was a record, a keeping of time. I’ve never really kept a private journal.

Instead, since I went to college – when I was 18 – I’ve been separated from my twin sister, and we write letters back and forth. We’ve kept many of them in notebooks, so we actually have an amazing record. We were also exchange students in Germany at 17, and we wrote home to our parents. So my record-keeping came through letters.

With Newspaper Diary, again, it’s not actually daily, but I clip photos and datelines and keep a sort of visual-log. It’s about time, not privacy. The idea of a “diary” makes it feel more intimate, but in practice, it’s something different.

And I should say – Anne Frank had a huge impact on me. The idea that the thoughts of a 13-year-old girl could matter, could be documented, published, and respected – that stuck with me. Even though the film version was Hollywood-ized – they cast a model, Millie Perkins, to play Anne – I still remember going to the set. A friend of my father’s, Joseph Schildkraut, played Anne’s father in the movie, and we visited during filming. So yes, journals – especially hers – made a big impression on me.

Speaking of memory – how do you see memory operating in your work? Photography both preserves memory and distorts it, since it captures only a single, specific moment. How has your relationship with memory changed over time?

In the 1990s, I focused a lot on memory because my mother was losing hers. I was reading a lot about it then, and also following the Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas hearings. That really shaped how I thought about memory – especially women’s memory. Anita Hill wasn’t believed. They said her memory was faulty. It made me think a lot about how women’s memories are discredited.

Photographs are evidence – but they’re incomplete. They only show a moment. So I began writing directly on the photographs, or asking the people in them to write on them too. You can see this work in my book Being in Pictures. I was influenced by Charlotte Salomon, a Holocaust victim who made over 700 drawings and eventually started writing directly on them – song lyrics at first, and then full text. I found that very powerful, and it gave me a model for how to work more directly with memory in visual art.

In some of my reading, I came across a quote from you that really struck me: “Romance is a powerful cover that masks the very bad deal marriage can sometimes be, especially for women.” I found that so compelling, and I’d love to hear more about your relationship to romance. It seems quite complicated – what is romance, actually?

Yeah... that quote came from a place of reflection. I think I was very carried away by the idea of one great love – that romantic dream. And my twin sister actually did have that experience. She met her husband before she graduated from college, and they’re still married. They love each other deeply, and she knew the moment she met him. It really did fit the romantic ideal. But my life didn’t. And I had to start unpacking why I was drawn to certain people, especially the man I married, and why it didn’t work out.

I realized I had bought into a story – a story full of overlays and illusions. That’s what my piece Romanticism is Ultimately Fatal is about. I used an illustration from a book called The Boy King Arthur – a very romantic image, with a horse and a rider. It looks like an N.C. Wyeth painting. It represents that ideal of being swept away, of galloping into love. But the title challenges that idea.

At the time, I didn’t realize how complex the word “romanticism” actually was – how much meaning it had in art history, music, philosophy. I was just thinking about it in the pop-cultural sense: the fantasy of everlasting, passionate love. And marriage, as I came to understand, is not about that. It’s a social contract – a financial arrangement. You share a house. You divide property. You support one another financially. Whether or not you love each other forever is, in some ways, irrelevant. That’s what I was getting at with that quote. It was a bit of a smart-ass line, but it came from real disappointment and clarity.

Can you tell me more about the process of making Romanticism is Ultimately Fatal? I know it marked a shift in your work – into collage – and it was also the first piece that really got people’s attention.

Yes. When Anthony Janson revised his father’s textbook, Janson’s History of Art, in the 1980s, he added a new chapter on photography. There were no women in the original edition at all – it was the major Western art history textbook used in classrooms – and when he revised it, he included my piece Romanticism is Ultimately Fatal. That was a big moment for me.

Five years later, though, they revised the book again, and it was taken out. So I thought I’d made it... and then I hadn’t. That’s how permanent that kind of recognition can be.

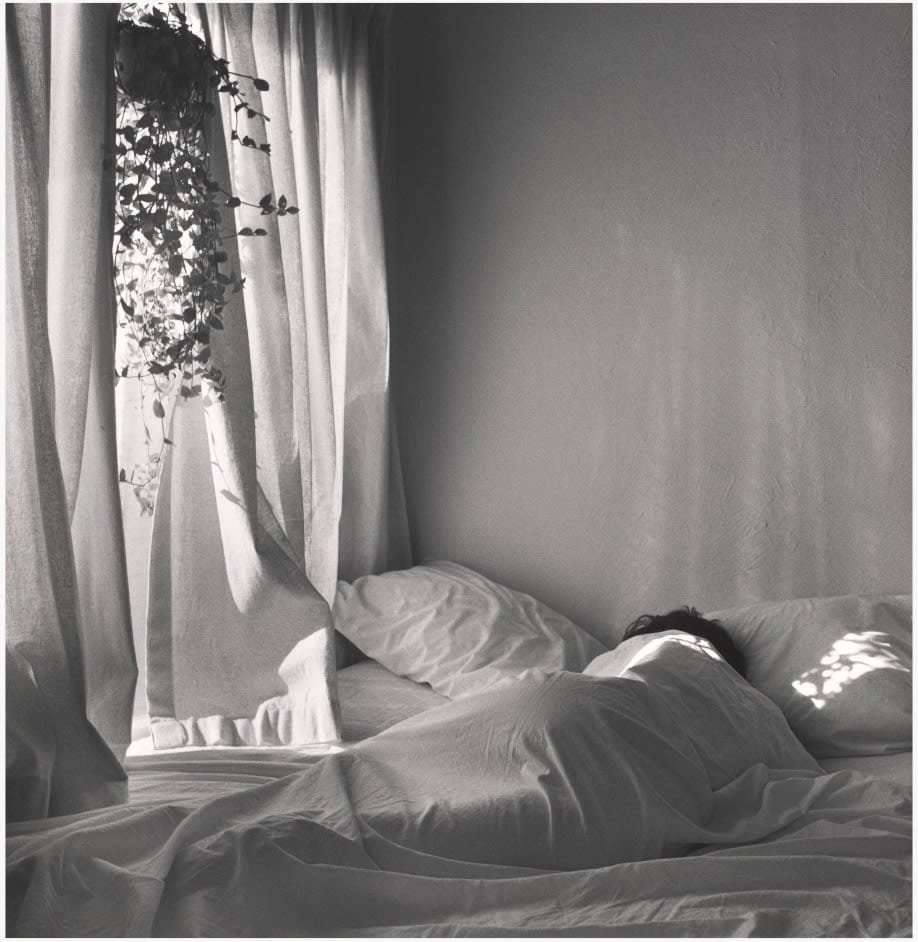

As for how I made the piece: I originally thought I would just paste things onto photographs. I’d taken a lot of images of women near windows – partly because windows are light sources, and photographers are drawn to them. Then I had the idea: what if the collage was behind the window, like something you could see through?

I found a material called Kodak Fine Grain Positive film. It’s a kind of transparency – everything white becomes clear. So I printed the photograph on this film and then layered it over the collage, which was placed where the window would be. That’s how I created the illusion of looking through the window into another world. That’s the technique I used for Romanticism is Ultimately Fatal and also for the series I call Dreams and Nightmares.

The original piece is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They’ve never shown it, but it’s beautifully presented on their website, with a strong curatorial statement. And I made a high-quality reproduction that I show now – it’s a single surface print, so it doesn’t have the layered depth of the original, but it’s still very striking.

I’m curious about this idea of museums owning work that they don’t display. I suppose it’s obvious, given the scale of most collections, but I hadn’t really considered how much of an artist’s work might never be seen once it enters an institution.

Yes, absolutely. Most of my work in museum collections just sits in storage. That’s part of what motivated me to donate more of it. I realized: I’m getting older. I don’t want my daughter to be burdened with all this work when I’m gone. I imagined it ending up at a Kiwanis thrift sale.

So I started offering museums gifts – “If you buy one, I’ll donate one.” But most said, “Our budget is already committed,” or “We can’t spend right now.” So I began just offering work outright. And because I already had work in places like SFMOMA, MoMA, the Whitney, it helped. I could write and say, “Would you be willing to accept this?”

And many did say yes. MoMA, for example, eventually accepted 60 of my works. They’d originally passed – years earlier, one of their curators had told me he was interested, but never followed through. Another looked at Journal of a Miscarriage and said condescendingly, “I think that’s about something we all know about, don’t we?” That made me put the work away for years – it was just too painful to show it to people who didn’t get it.

Eventually, though, an anthropologist named Ruth Behar became interested, and Journal of a Miscarriage was published in the Michigan Quarterly Review. That helped bring it back to life – twenty years later, it finally started getting the recognition I always thought it deserved.

That’s such a powerful story. It’s also been interesting hearing how people discover your work – like that gallerist who saw your piece in an old book.

Yes! Joseph Bellows, a gallery owner in San Diego, saw my work in a 1970s book called Vision and Expression, which was put together by Nathan Lyons at the Eastman House. That book came out around 1972, and two of my photos were selected. Decades later, Bellows saw them, got in touch, and actually flew out to meet me. He bought a bunch of pieces and took more on consignment. Ten years later, I reclaimed the consignment pieces and offered them to MoMA – that’s how they ended up acquiring that group.

So yes, these old books can have long lives. You never know when someone will stumble across something and reconnect with the work.

From everything I’ve read, your work has been deeply important to the feminist movement. But I’m curious about your thoughts on feminism today – especially given the current political climate, and critiques of whitewashed, heteronormative cis-feminism. How does the movement today compare to the second-wave feminism you were part of?

Well, when we were part of the second wave, we didn’t know we were part of “the second wave.” We weren’t thinking of ourselves as the next suffragettes. It evolved as we went.

Meeting Miriam Schapiro was pivotal for me. She saw my work at the San Francisco Art Institute – specifically Journal of a Miscarriage – and was very excited by it. She invited me to New York, even hosted a party in my honor. I brought the male gallery director I was working with, and she told me, “Joanne, this party is only for women.” That moment really stayed with me.

I wasn’t immediately a feminist. I was cautious at first, unsure. But the feminist art community welcomed me. People like Miriam made space for women in a way that was crucial. That changed me. It helped define who I became.

Lately, I’ve been reading a biography of Adrienne Rich. She was 11 years older than me. She married, then later came out as a lesbian and became a key feminist figure. Her journey really resonates – especially the way her feminism evolved. She initially supported the anti-pornography movement led by Catherine MacKinnon, but later recognized how criminalizing porn could harm non-normative sexual expression. That’s an important shift.

I’ve had colleagues like Carol Jacobsen, a filmmaker and activist, who opposed MacKinnon’s position. She works with criminalized women and believes strongly in sexual agency. So, I’ve been surrounded by a range of feminist perspectives. Over time, I came to believe feminism is a lens – a way of noticing what’s been excluded.

There are people who say, “I don’t want to be labeled a woman artist – I’m just an artist.” I understand that. But in a world that has historically ignored women’s contributions, claiming that space is important. For me, it was empowering. Feminism made room for me.

Joanne Leonard: Vintage Photographs and Early Collages

HackelBury Fine Art, London

29 May – 8 July 2025

Exhibition Events:

5 June, 18:00–20:00 – Artist Reception

6 June – In Conversation: Joanne Leonard with Griselda Pollock and Fiona Rogers

Visit hackelbury.co.uk for more information