The life of an artist is lonely. We spend an immense amount of time in the studio, inhaling paint fumes, and listening to the same albums on repeat, wrestling heavy, sticky materials. We still shoulder the myth of the singular genius, or the romantic starving artist; to be a successful artist, you must be depressed, or broke, or heartbroken, and of course, soul-shatteringly lonely. Only then can great work be created.

I know – how awful! Obviously, great work doesn’t only come from misery and self-destruction. If that were true, we’d all be fucked. In fact, great work finds its most fertile ground in love and trust and community.

Some of the best models of the way love fosters creativity are queer couples, who work outside of the heteronormative frameworks of the art world. Artist Ian Lewandowski, who lives and works with his partner and fellow artist Anthony Cudahy, told me that the weight of those mainstream expectations is hard to let go of: “a lot of that is internal – it’s part of a larger capitalist structure, the myth of the singular genius. For me, understanding that makes it easier to navigate. When I feel competitive, I go back to myself, to what I’m trying to do.”

Modern art is littered with examples of prolific, collaborative queer couples, many of whom grappled with much greater social ostracism (or criminalisation). Think of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, or Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg: these couples created work for each other, with each other, breaking with mainstream expectations about what art should be.

Today, queer artist couples are able to live more openly. I don’t want to say that we have solved homophobia and that now we all can hold hands and dance around in a little circle. I think Barcelona-based artist Isabel Rabassa, who lives and works with her partner María Cuéller, put it best: “It’s not about being victims or comparing hardships. We’re two women, two lesbians, and yes, people project things onto us — sometimes admiration, sometimes envy — but it’s about supporting each other.”

While all four contemporary artists I’ve mentioned create individual work, sharing their lives with a romantic partner who is also an artist has allowed both couples to shun the pitfalls of the cult of the artist. “For almost 12 years now,” Anthony told me, “we’ve always prioritized and supported each other’s practices. If you don’t have family money, it’s one of the only ways you can have the security to give yourself the time and space to work on your art.” María echoes him, telling me “it’s a liberation, meeting someone who opens you up. You have to be open to receiving and giving. We didn’t want to be oppressed or to oppress each other – we wanted to support each other.”

In her essay “Love as a Practice of Freedom,” bell hooks declares that a love ethic is key to dismantling our culture of domination and capitalist systems. She quotes M. Scott Peck, who defines a love ethic as “the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own, or another's, spiritual growth.” These artists not only approach their relationship with a love ethic, but also their artistic practice, placing equal importance on their work and that of their partner.

Working together, sharing studio space, bills, and labor has allowed the four artists the creative freedom to create without fearing financial ruin. I often wonder how artists without a massive trust fund do it. The art world is unfairly built to uplift those who are already rich and oppress literally everyone else. Working in a duo, and approaching the work and practice from the place of both love and unfettered support, allows for not just amazing creative work but also stability.

Anthony, a figurative painter, consistently features Ian as his primary subject. “With painting, there’s this level of exploring the idea that even the person you know most intimately is still inherently a mystery to you.” says Anthony “Sitting with that mystery is a way to show love — not defining someone so strictly.” In one of my favorite paintings of his, Ian lounges topless across the lap of the couple's boyfriend, Alex. Alex is pantsless, his cock peaking out from between his legs. Ian stares directly at the viewer, while a small Anthony is shown painting in the mirror behind the two. Not the subject, nor absent from the painting, Anthony places himself in conversation with his two subjects.

Ian is a photographer whose work features striking portraits of his queer subjects. Similar to Anthony, his work focuses on intimacy and individuality, putting queer people and their lives on display. Both artists use their relationship as the scaffolding to their practice. Their relationship has acted as the structure for their individual practices to evolve.

If Anthony and Ian show us how queer love can structure and sustain two separate practices, painters Isabel Rabassa and María Cuéllar offer something different — a radical act of co-authorship. Their shared studio, which doubles as their home, serves as a kind of sanctuary: a space of intimacy, resistance, and total creative freedom. Here, they are free to make — together or apart — without the scrutiny or expectations of the outside world.

Emotional intensity is the foundation of their practice. Together, they’ve developed a collaborative language driven by trust, instinct, and deep attunement.“We both bring ideas, and we explore how to translate them together,” says Isa. “It’s about sharing a vision, not dependency.” María echoes this, adding, “for me, it’s about working together to create values in this contemporary space — in how we relate, in how we speak and communicate with each other.”

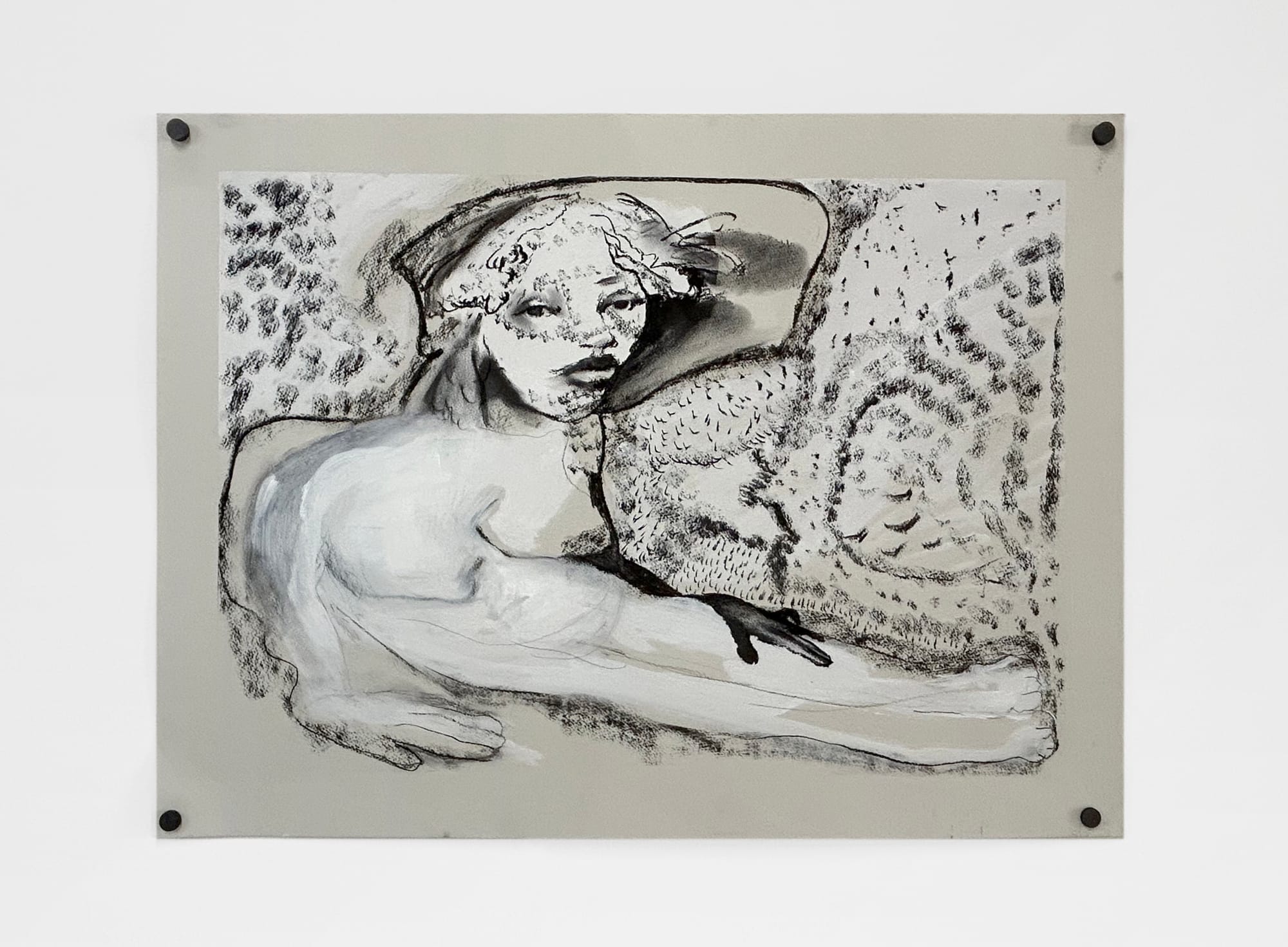

Their most recent painting, Esfinges (“Sphinxes”), shows two hybrid female-beast figures bathed in soft, ethereal tones. One crouches, wings cloaked in lemon yellow next to her partner, a red clawed woman who stares off into the distance. While different in coloring, expression, and animal qualities (one has cloven feet while the other massive paws) the two are intrinsically linked, with an obvious union in their mythical world. This painting exemplifies Isa and María's relationship: two artistic voices coming together to build their own queer and magical reality.

What can these novel ways of work teach us? If art is about creating something new, groundbreaking, and exploratory, why only limit that to the work? Why not apply that same philosophy to social structures? Greatness does not spring from solitude but rather from collaboration. These couples create a rebellious blueprint of how to work against systemic capitalist hierarchy that dominates the art world – they teach us the importance of the collective, of the shared, and of the community.