Parisian painter Johanna Tordjman is a storyteller. While painting is her chosen medium, speaking could easily be her second. Her enthusiasm for the stories of others – and her own – is infectious.

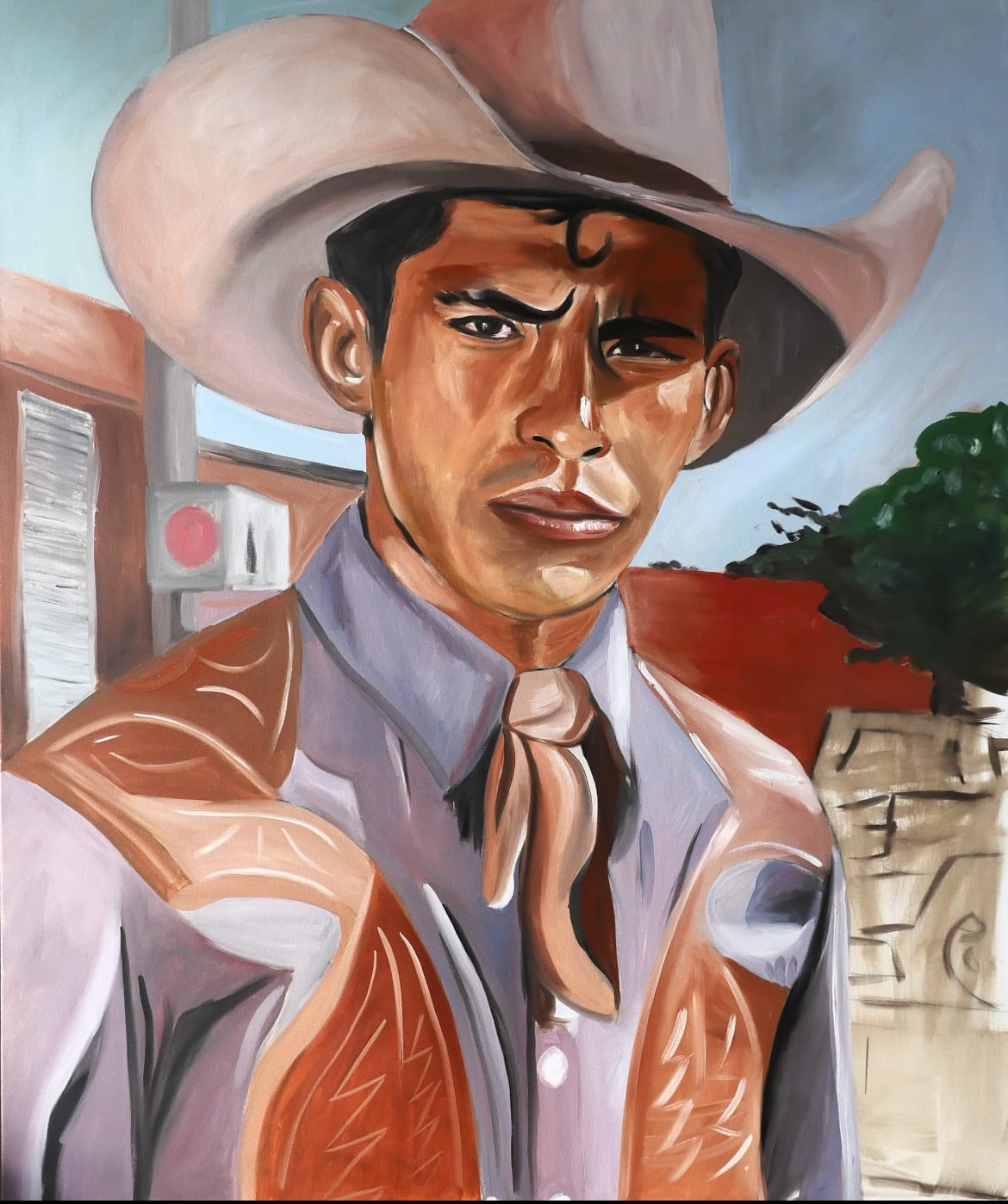

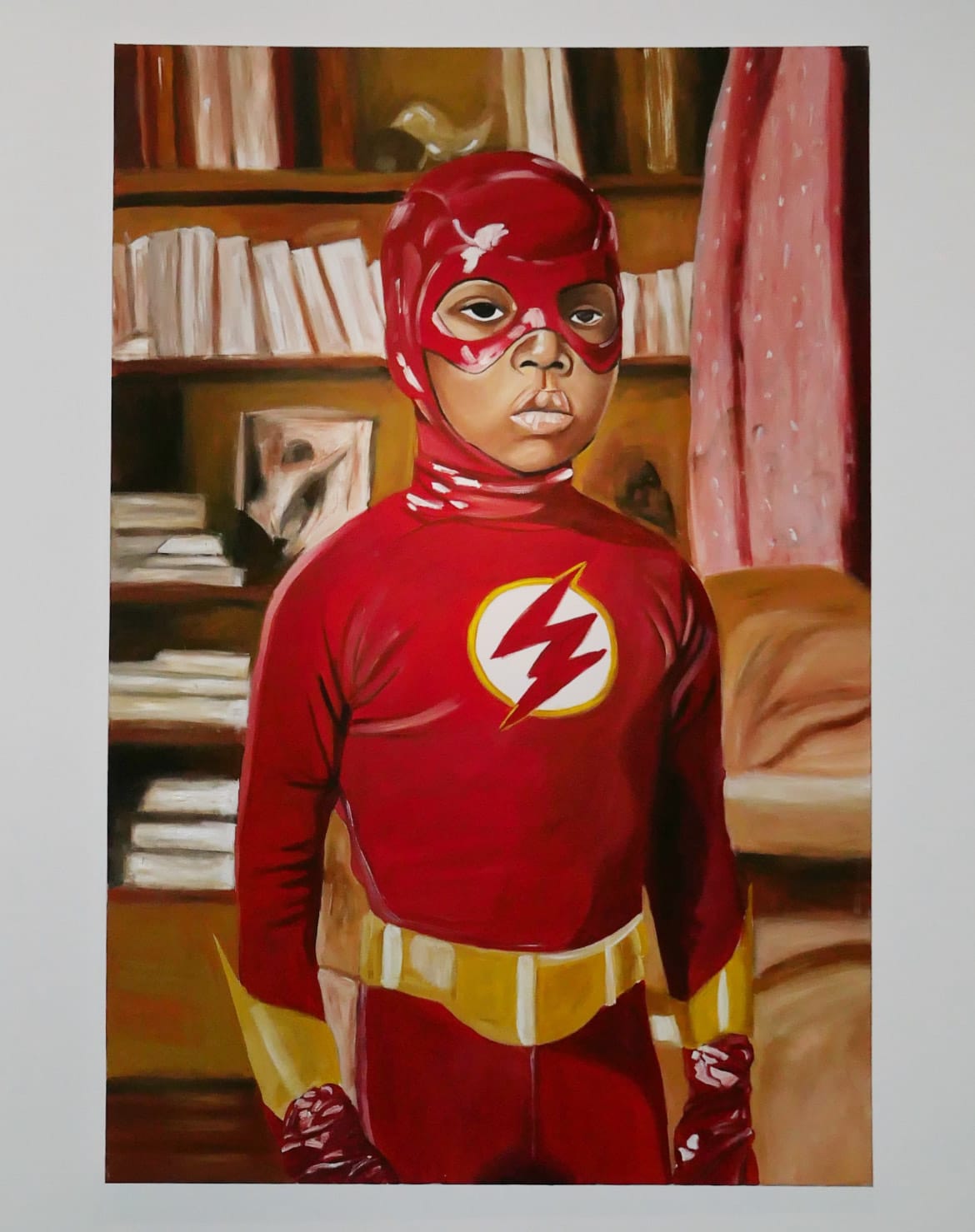

Though Johanna is an icon in her own right, she chooses to turn her gaze toward the forgotten, delving into pasts left behind in dusty family photo albums and shoeboxes tucked away in closets. In her most recent show, October 61, the artist showcased 30 paintings drawn from the photos of Parisian migrants.

For Johanna, “people die when you don’t talk about them anymore.” She paints not just to be remembered herself but to rebuild the memories of those who came before.

Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

ISABELLA FOX ARIAS: Did you grow up in Paris?

JOHANNA TORDJMAN: I was born and raised 40 minutes from Paris, but some of my family are in California. As a kid, we used to travel to the US for holidays, which allowed me to experience two very distinct cultures at a young age. But I’m entirely French, and my heritage is from North Africa, like Algeria and Tunisia, and this heritage is what my recent show is based on.

I know you started painting around 25, which goes against the common artist narrative of coming out of the womb holding a paintbrush. What drew you to painting?

From a very young age, I always had the artist vibe. I always pictured stories in my mind with everything I did, from drawing to playing with my dolls. But I was raised by my mom only and we were not wealthy. Being an artist was not even an option, I didn't even know it could be a job. So, I was like, I like to draw, I want money, so let's be an art director, you know? And so I studied graphic design and art direction in general. Now I’ve been doing that for 15 years.

At first, I started painting on the side because I had stuff on my chest that needed to be expressed. Words were not my thing. For my 25th year, I painted every time I felt a new emotion.

And now, 10 years later, you work full-time as an artist?

Yeah, which is ok! When Covid happened, I could see myself painting all day and making bigger projects, but at the time I was working a 9-7 job. I would never have been able to do what I’ve built since then as a painter. So, I took the decision to quit my job and focus fully on my painting.

You mentioned stories as one of the things that drew you to painting. What does storytelling mean to you in the context of visual art? How do painting and storytelling intersect in your practice?

Every exhibition starts from a story. I could see myself sometimes as a film director – like, okay, I have this story to tell. But the medium which I'm most comfortable with is painting. Sometimes, for example, in my recent show, there’s a film that is going to be projected because it helps me tell the story. In the end, whatever the medium, the story comes first. I paint people and these are real people from the real world. I have to honor their story. Storytelling is just what I love. I am so interested in the people that I meet and I always gain so much from a conversation that I want to share it.

How do you find the stories you want to share?

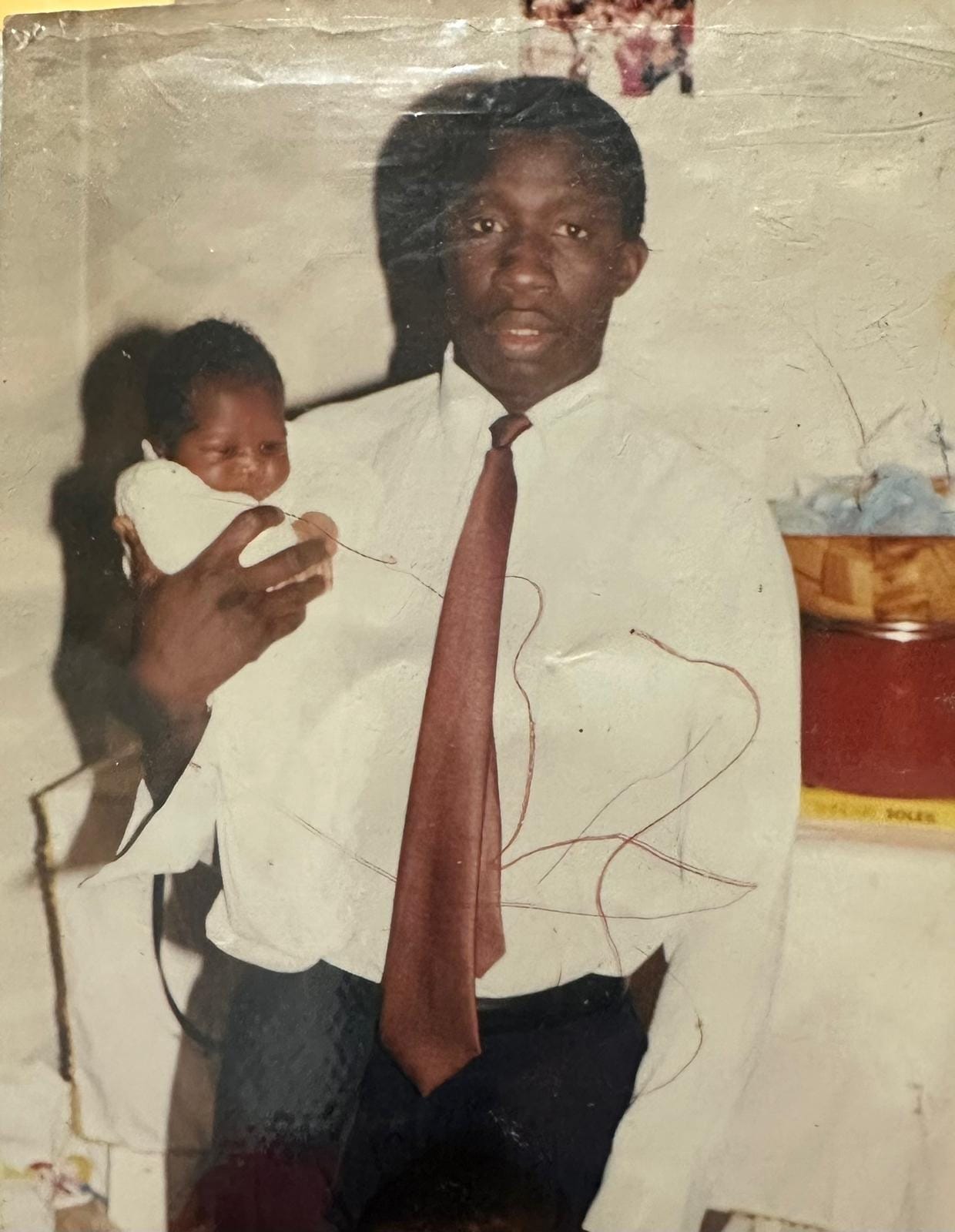

It's different from each project to the next. With my project 25h01, 25 hours and one minute, the exhibition talked about the objects people brought when they left their homeland. For this, I took inspiration from my grandmother who left with a stool, just a stool, and some photographs (which acted as the foundation for my most recent exhibit, October 61). We always heard so many stories about this stool, which was not a good stool, but it was the only piece of home that my grandmother could bring with her. I had a conversation with my grandmother that I recorded about her stool and I realized that there must be so many other people with similar stories, so I started to ask around.

My grandmother came over in ‘61 and she was one of the first big waves of immigrants arriving in Paris. But it hasn't stopped, people are still arriving today. Through my sister I was connected with a space called CADA, which is a shelter for asylum seekers. I asked each person I talked to the same question: “what did you bring with you and how do you feel about this objectt?” Some people had long answers and some just a word. I’m not a journalist so I was not asking anything else. My job was to create a space where someone feels comfortable to share a piece of their intimacy. I was asking them to tell me the story of their exile through the prism of the object.

There was a woman named Fadwa who came from Syria and her object was a butterfly-shaped soap. She told me that this was the soap that her mother gifted her so that she would never forget the smell of her mother. A lot of the stories are like this. This show was the first time I decided to tell a big story. It changed me as both a woman and an artist.

How old was your grandmother when she came to Paris?

She was 26. She was young, she had two little kids. She was a badass, you know, and she was so cool. I wanted to honor her, but also all of the parents and grandparents who gave up everything for us to have a better life. This is how it all started, where the storytelling came from. To me, a good story is one that triggers a conversation, that makes you want to find out more about your roots and heritage.

After you’ve collected your stories and your artifacts, how do you transform them into your own work?

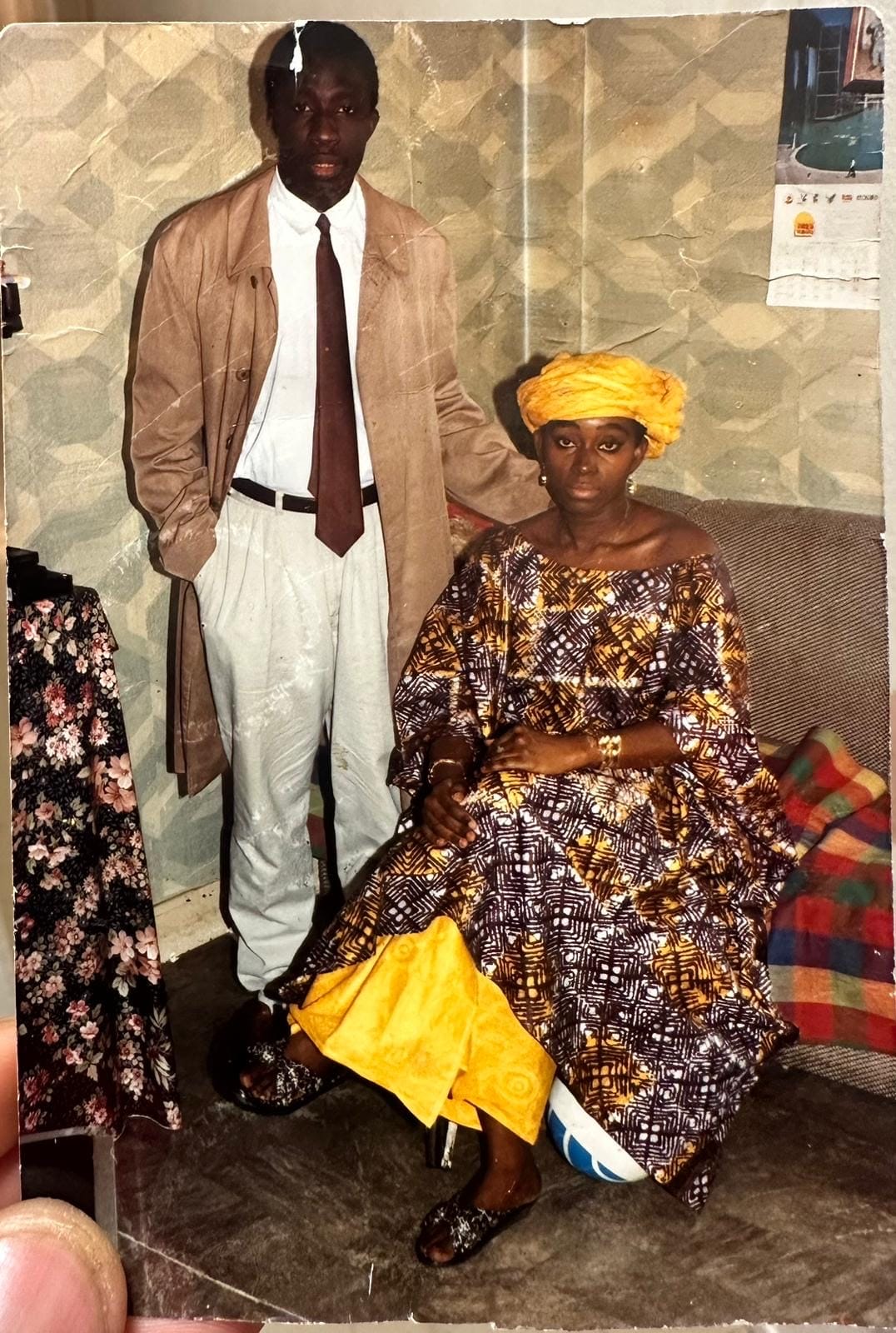

The images always come with the stories. There’s a photo of the mother of my friend on her fifth day in Paris. There was something intangible about that photo that I was drawn to. I can see the world through her eyes and I can try and imagine how she felt. Every story shared, and every photo I’m shown, carries so much.

Your portraits often challenge traditional European notions of representation. Through fragmentation and composition, they resist the idea that a portrait is simply a direct likeness. How do you approach composition? Do you consciously push against Western portrait traditions, or is this something that happens organically?

I have a natural taste for weirdness. Through painting, you can get so close to that one fragmented emotion, one instant, one captured tiny moment. I love it. If I wanted to reflect the whole reality I would take a picture, painting is not needed now to represent the exact reality. I will never master the technique of hyper-realism. I love accidents and in painting you can provoke them, you can create them, and you can embrace them. Everything starts from an accident. All of these real life scenes, like taking photos of family, there is no pressure for them to be perfect. My compositions capture memory.

What I find interesting is that you’re drawing from film photos that were never meant to be shared publicly — unlike the way we use Instagram or Facebook today. These are images meant for the family, to be kept at home or even left in a box and forgotten. Now, you’ve brought them out into the world for a wider audience.

I barely retouched the framing. There was no platform to share everything. Bringing all these memories back to the surface makes me feel like people will want to go through their family photos. And that's my goal, to make people dig up their past.

There is a writer I like, John Berger, who said, “We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves.” Despite not creating self-portraits, your gaze as an artist is always present in your work. How do you navigate the balance between being a witness to your subjects and imprinting your own perspective?

I see myself as a witness of my generation. By choosing to paint the stories that I do, I am witnessing how the world is evolving. I am also telling a bit of my story through everybody’s stories. They all carry a bit of my story as well. Everything always starts for me from my grandmother, my own family, and my own heritage. With my subjects, I always share my story first. They feel it is okay to share more of them because we come from a common place.

It's always been so natural to meet people and have them share because I don’t come with the want or need for them to tell me the hardest part of their lives. Instead it's, “this is my story that I want to share.” As well, being a minority myself, when I meet people from minorities, we all have something in common.

It seems to me that you leading with your own vulnerability creates a space that allows others to feel comfortable to share. You are presenting yourself as an equal to your subjects.

Yes, exactly. I also don’t want it to seem like a tool to get people to open up, as this would be manipulation. I think people who know me know that everything always comes from the heart, sometimes almost too much.

In your documentary project across America, you asked your subjects, “What do you want to be remembered for?” So, Johanna, what do you want to be remembered for?

So funny, you know nobody has asked me this before!

Really?

Yes! I was happy because I never thought of the answer. But, I think I want to be remembered as someone doing something. As coming from the heart, respecting the people and the cultures, and trying to pay tribute to the ones who really mattered. To me, people die when you don’t talk about them anymore. So by painting people and saying their names, they don’t just become mysterious images. Like the Mona Lisa – we still wonder about her! But I am trying to give answers.

My practice is reporting people I admire to the next generation. I think that’s who I am? Well, I don’t know who I am, but it would be this if I am anything. I want to be remembered for trying to connect more and more in a world where everything going on is super scary and dividing.